Episcopal Diocese of Washington DC, Bishop Mariann Budde, in her sermon at Washington National Cathedral’s Service of Prayer for the Nation on January 21st, called on all Americans to strive for a renewed unity based in honesty, humility and respect for human dignity – and she directed her final words to the newly inaugurated President, who was seated in the front row.

A segment of Bishop Budde’s sermon included this message:

Millions have put their trust in you. And as you told the nation yesterday, you have felt the providential hand of a loving God. In the name of our God, I ask you to have mercy upon the people in our country who are scared now. There are gay, lesbian and transgender children in Democratic, Republican, and independent families, some who fear for their lives. And the people who pick our crops, and clean our office buildings; who labor in poultry farms and meat packing plants; who wash the dishes after we eat in restaurants and work the night shifts in hospitals. They…may not be citizens or have the proper documentation. But the vast majority of immigrants are not criminals. They pay taxes and are good neighbors. They are faithful members of our churches and mosques, synagogues, gurudwaras and temples. I ask you to have mercy, Mr. President, on those in our communities whose children fear that their parents will be taken away. And that you help those who are fleeing war zones and persecution in their own lands to find compassion and welcome here. Our God teaches us that we are to be merciful to the stranger, for we were all once strangers in this land. May God grant us the strength and courage to honor the dignity of every human being, to speak the truth to one another in love and walk humbly with each other and our God for the good of all people of all people in this nation and the world.

As Tom Pepinsky noted in his reflection, “We Kneel to No Pope, We Kneel to No King,” Bishop Budde was quickly disparaged by the President and his followers, with Senator Josh Brecheen of Oklahoma even filing a House resolution (H. Res. 59) condemning Bishop Budde’s sermon at the National Cathedral as “a display of political activis and condemning its distorted message.” Yet, my friends, as Pepinsky observes, “Bishop Budde was acting from her solemn responsibility as the embodiment of America’s political and religious establishment, reminding the new administration of the values upon which the United States was founded and its responsibility to uphold them. This was not an act of resistance. It was an act of leadership on behalf of the closest thing that the United States has to a national church”.

Pepinsky’s essay reminds us that the separation of church and state is a foundational principle of our nation as articulated by our nation’s founders and embodied in our national history. Many Christian nationalists today find the separation of church and state to be an obstacle and appeal instead to a version of Christianity very much associated with the principles of empire, the same Christian empires that came to these shores from the Roman Catholic principalities of Portugal, Spain and Protestant England, legitimating slavery, genocide, and commercial destruction of vast natural resources as God’s will for providing for God’s chosen people.

The Constitution of the United States was drafted by wealthy, landowning white men, many of whom were slave owners. However, their faith was not Christian nationalism. Their aspirations reflected the conditions of the founding of this nation. Namely, they kneeled to no pope, and they kneeled to no king. That is because they were mostly Episcopalians. The Episcopal Church of the United States of America is, as Pepinsky notes, is the closest thing that the United States has to a national church, “This is a historical fact, and a living contemporary practice.”

There is an institution in Washington, DC called the National Cathedral. It is truly a national cathedral, established by an Act of Congress, aligned with the vision of the Founders for our national capital. The denomination of the National Cathedral is Episcopalian. Bishop Budde is the bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington and as such, the National Cathedral is her seat as bishop of that diocese. The establishment of the United States of America coincides with the establishment of the Episcopal Church, because the Episcopal Church is the Church of England in the United States.

Pepinsky’s essay additionally reminds us of our church’s unique history. Anglicanism is the belief system and liturgical practices based on the Church of England. As everyone who has learned European history knows, the modern Church of England emerged through a schism between King Henry VIII of England and the Pope Clement VII, which produced the English Reformation. Driven by various spiritual and worldly matters, Henry refused to recognize papal authority over religious affairs in England. Anglicanism recognizes apostolic succession, but it does not recognize papal supremacy. The King of England is the supreme governor of the Church of England. As head of the church, though, and bishop of the See of Canterbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury kneels to no pope, and we in the Episcopal Church – reminding you again – kneels neither to the King of England nor to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, a newly independent United States of America had rejected the King’s authority over the thirteen colonies and subsequently separated from the Church of England, which required an oath of Supremacy to the King by all clergy. An early American Anglican clergyman could not take the Oath of Supremacy, because it was essentially an oath to the monarchy. The Church of England was disestablished in the United States, and the Episcopal Church was founded through a series of events that preserved apostolic succession and conceived a system of governance very similar the newly established nation. From that time forward, the Episcopal Church in the United States operated independently of the Church of England. In later generations, it joined with the Anglican Communion – a relationship of international expressions of the Anglican/Episcopal provinces around the world, the remnant leftover of past Christian Empires come and gone.

Finally, as Pepinsky underscores, in Bishop Budde’s sermon, she “articulated a national understanding of the responsibility of faithful leadership towards the American people – the faith tradition of a republic that welcomes all those seeking new opportunity and the chance of a new life for themselves and their children.”

Bishop Budde’s sermon additionally echoed the concerns of the Executive Officers of The Episcopal Church in a letter they issued on January 21st letter to the church, issued in response to the President issuing a barrage of executive orders within the first hours of having taken office, many orders targeting migrants, refugees and other peoples.

The letter released by the Executive Officers of The Episcopal Church urges “Our new president and congressional leaders to exercise mercy and compassion, especially toward law-abiding, long-term members of our congregations and communities; parents and children who are under threat of separation in the name of immigration enforcement; and women and children who are vulnerable to abuse in detention and who fear reporting abuse to law enforcement.”

The letter concludes by encouraging congregations to use the resources of the Office of Government Relations and the Episcopal Public Policy Network and to embody the Gospel through direct witness on behalf of immigrants in our communities. This letter was written in response to the executive orders, The order included measures seeking to suspend the federal refugee resettlement program, declare a national emergency at the U.S-Mexico border, block an “invasion” of migrants into the United States, end the right to birthright citizenship that is guaranteed by the Constitution and resume a policy of making asylum-seekers wait in Mexico for their cases to be heard. Other executive orders were related to the federal work force, the economy, energy policy and the environment and they included some measures targeting transgender people. The government, intends to recognize only two sexes, male and female, and seeks to end protections for transgender inmates in federal prisons.

A growing number of Episcopal bishops are speaking out in response to the new administration’s threat to fulfill a campaign promise of mass deportations of undocumented immigrants, possibly including raids in churches and other places that previous presidents had deemed off-limits for such enforcement. These bishops speaking out include the bishops of Arizona, New York, Massachusetts, Western Massachusetts, and Southern California. Now, the President of the United States has suspended the country’s 45-year-old program of refugee resettlement, which has long enjoyed bipartisan support. In addition, the Department of Homeland Security issued directives reversing the Biden administration policies that avoided immigration enforcement in “sensitive” or “protected” areas, including schools, hospitals and houses of worship.

I want to say to you that Trinity Everett will remain a spoke in the wheel of our diocesan commitment out of the hub of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Seattle to provide sanctuary, protection, and advocacy to immigrants and refugees. Without a warrant signed by a judge, we will not permit entry of federal ICE agents into our buildings. Bishop Budde is correct when she says that people are afraid now. This is not in the abstract. These orders directly affect people seated in this sanctuary today, maybe even the person sitting next to you. For example, initiatives approved by the new Presidential administration includes a directive that unless both sets of grandparents were born in this country, you are at risk for deportation. Refugees from war that this church sponsors – right here – and that we support are at risk for deportation. Trans people known and beloved by members here and now are and will be subjected to having trans identities revoked. Same gender couples married before God at this altar are at risk of having their marriages invalidated. Even Indigenous Americans are being threatened with loss of US citizenship our their lands are even now being reclassified, opening them for mineral and resource extraction. Removing the cap on the cost of insulin and other medications and life prolonging procedures threatens the health of elders right now sitting in this space and in our community.

It is hard enough for women and LGBTQ persons and people of color in this country to endure the daily onslaughts of racial and gender discrimination, much less experiencing the additional burden of a racist, sexist national leaders informed by an imperial version of Christianity. After my personal experience of the bishop search process in the Diocese of Rochester last year, I posted this message on social media:

Resume, experience, expertise, competency, integrity, values and commitment seem less relevant than the state of my hair in the bishop search processes in which I’ve participated. In one instance, I was wearing four braid loops pinned up (a style of my traditional Indigenous tradition) when a young male search committee member remarked while laughing, “What’s going on there? That’s wild! Ha! Ha! Ha!” In a different interview process, I was wearing two braids with a small feather ornamenting one. An older white woman on the search committee who contacted my references then asked each of them, “Does she always dress like that with her hair?” In the most recent discernment process, I decided to wear just one plain braid over my shoulder (as in my profile picture). One clergy person queried of another, “Why does she wear her braid like that?” They were quite troubled by it. My friends, cultural competency means understanding and respecting other cultural values and ascetics while not expecting others to conform to dominant culture assimilation (racial biases often referred to as “professional” and is essentially racist). In my culture, long hair and braids are a hallmark of cultural pride and connection to ancestors, community, identity, spiritual values and honor. If being a leader in dominant culture church means cutting my hair or making my hair less “wild”, then it’s not a church I want to lead.

With their permission, I would like to share an email that I received from parishioner Linda Gabourel and her husband Po that emailed privately to me in response to my post:

Dear Rachel:

Having heard about your recent Facebook post regarding the comments about your hair style during the Rochester discernment I believe voices need to be raised. I don’t have Facebook, but Kate copy-pasted your comments and sent them to me. (Thank you, Kate).

My initial response was to be angry on your behalf and yes I am angry and dismayed that comments like that would come from people who should know better and do better. There was nothing subtle or veiled about the insult to your indigenous heritage from those few petty individuals. I am so sorry for the pain and discouragement it is causing you. I have some thoughts to share for whatever they are worth. First and foremost, don’t ever let them win! This is where the strong stand up, continue to speak out, lead the way and continue to educate those who need their eyes opened. [Ironically, I say] You are one of the strongest women I have known in my lifetime. If leaders like you give up our church will suffer. Never forget that you are extraordinary, strong, and your voice and example are indispensable to the Episcopal Church moving forward.

When I was in medical school and in training, women like myself, put up with a lot of sexist comments and harassment and we never felt we had the power to change that. It was work hard and keep your head down. What we did do was to stay, keep coming and fight for our place. My husband had a patient during his residency at the Seattle VA hospital, that refused care from him as he, quote, didn’t want a “gook” touching him. He assumed Po was Vietnamese. Po wrote basic admission orders and a note including “patient refused care from a gook”. It hurt. He kept moving forward and physicians of color kept coming. I have great faith in people and believe that they can learn and they can change. With leadership like yours and people like those at Trinity, we will keep coming and swarm the church with love, inclusion and tolerance. To do that they need to hear from people like you. You can change people one at a time. You have a voice. You be who you are. No conformity required!!! Loud and proud right? The fight is a hard one so what can I do to help and support you?

My friends, I do not get emails like this.

Last weekend, I wasn’t here. Father Allen presided and preached in my place, because I was away attending an annual gathering of Indigenous Episcopalians called Wintertalk, which has traditionally been held on the weekend of the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday. We experienced the presidential inauguration on MLK Monday and the release of the executive orders that followed, including an order opening up long-protected Indigenous lands for mineral and fossil fuel extraction and the removal of any mention of climate change science from the White House webpages. The events and conversations of this past Wintertalk caused me to face a terrible reality – I have not ever in my professional life felt safe enough to share my full self within the predominantly white spaces in which I have worked and which characterize The Episcopal Church, including here at Trinity Episcopal Everett. There is much for us to explore about that which we might chose to do as we go forward together. For now, I would simply remind you that the Episcopal church’s statement that “All are welcome” needs to apply to clergy in our diocese, as much as anyone else. Allen Hicks who is Citizens Potawatomi and me – a Shackan First Nation woman – are granted the authority and responsibility by the canons of this church to lead this congregation in the teachings, values, and practice of our faith. Yet, I am challenged; I am not seen as an Indigenous woman. I disappear in the words of people who continually say that they do not see color. You must see color. I guarantee you that we see your whiteness.

The actions of the new national leadership are disheartening, and the actions of our government will likely continue to brutalize the vulnerable and further privilege those who are already abundantly privileged within a racist and sexist society. However, Bishop Steven Charleston (Choctaw elder and retired bishop of Alaska) reminds us of the ultimate mission of our church in the following reflection that he posted this past week:

“Shock and awe is a military tactic. Comfort and awe is a spiritual alternative. The military option supports the will to dominate. The spiritual option supports the commitment to liberate. We share with all people an awesome grace: the path to peace, on the walk of truth and reconciliation, with justice lived for the sake of all creation. We do not seek control, but something much more transformational and enduring. We seek kinship.”

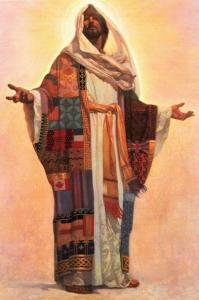

My friends – my kin – the Episcopal Church is a faith tradition formed by and for revolution, rooted in the teachings of a brown-skinned socialist Jew living in the Middle East under occupation of Empire. This is our Messiah. His message of love of one’s neighbor and faithfulness to teachings of mercy, compassion, and peace were so threatening to those in power in his day that he was executed by the Roman government for sedition. St. Paul and eleven of the apostles followed in his steps through their own journeys of resistance, service, and hope until they, too, were martyred and their faith was ultimately retooled to fit the purposes of empire under Constantine I.

Resurrection, like revolution, is threatening to those who would rule by force and reject the spiritual and divine quality of mercy. Violence and death have never had the last world, not in our wisdom traditions and not in world history. The Episcopal Church – in case you are Episcopo-curious or you have friends who are Episcopo-curious – the Episcopal Church takes seriously, what it means to be the Body of Christ; we hold dear the responsibility of our Baptismal Covenant to strive for justice and peace among all people and to respect the dignity of every human being. We are dedicated to the commandments of the Savior we follow – to love God with all our heart and mind and being, and to love our neighbors as ourselves; and finally, in fidelity to the core principles of the Episcopal founders of the United States of America, we kneel to no ruler but Jesus Christ alone.

We follow the liberating strength of God’s love and come together every week to celebrate the true freedom that is to found in unconditional acceptance and mutual support as a spiritual community equal before the eyes of God. We are a people born of both spiritual and social revolution. We are the Episcopal Church, and in the face of all those who would exclude and deride, harm, who would endanger emigrants, LGBTQ persons, women and children, the elderly, the ill, the hungry, the homeless, the jobless, the poor, the addicted, the imprisoned, the Indigenous, the foreigner, the vulnerable. More than a logo, more than a slogan, more than a glib bumper sticker – we say on behalf this nation and of our church, “All are welcome!”

We say, “All are welcome!”

We say, “All are welcome!”

Let this be the revolutionary cry of our times!

*******************************************************************************

To view the YouTube livestream version of this sermon, go to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W5T6lC-RWdc

To view the sermon given by Bishop Marianne Edgar Budde at the National Cathedral, go to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwwaEuDeqM8

To read the letter released by the Executive Officers of The Episcopal Church, click on this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwwaEuDeqM8

To read the essay, “We Kneel to no Pope, We Kneel to no King” by Tom Pepinsky, click on this link: https://tompepinsky.com/2025/01/22/we-kneel-to-no-pope-and-we-kneel-to-no-king/