“God rest ye, merry gentlemen – let nothing you dismay.

“God rest ye, merry gentlemen – let nothing you dismay.

Remember, Christ our Savior was born on Christmas Day!”

For many of us, the Advent and Christmas seasons can often mean the onset of a couple of unwelcome guests – Stress and Depression. In the midst of what is presented as a joyous time, we can often experience a burden of expectations (imposed by others or by the self) that can create a long list of demands upon us – parties, gatherings, watching a seemingly endless series of traditional movies, attending the theater or ballet, shopping, baking, Christmas pageant preparations, cleaning and entertaining, as well as decorating and driving around looking for “needed” items (just to name just a few stress triggers).

It’s so important to remind ourselves and our families that the Spirit of Christmas is not some kind of divine bullwhip driving us into a manic frenzy of over-commitment and consumerism. Rather, the Spirit of Christmas is a gently-whispered invitation to enter the quiet contemplation of the Holy Nativity scene – the hidden Crèche within each of our hearts, wherein lies the sleeping Christ Child.

Through some practical spiritual practices, we can help ourselves to minimize the stress that accompanies the Season and ensure that the King of Peace really is born into our world (into and through each one of us) this Christmas. To this end, here are 10 Spiritual Practices I have put together for your consideration in this Season of the Spirit.

1) Acknowledge you feelings. Whatever your feelings about this time of year or Christmas, acknowledge them. If someone close to you has recently died or you can’t be with those you love, realize that it’s normal to feel sadness and even grief at significant holidays and anniversary dates. It’s alright to take time to mourn or express your feelings. Try not to “force yourself” or permit others to force you to be artificially cheerful just because it’s the holiday season. Choose how you will manage your feelings and care for yourself, so that you can be authentically present to others (and to God), honoring your own needs as well as those of others.

2) Reach out. If you feel lonely or isolated, seek out community; come to our various church services or other social events around you – even if it’s just for a little while. These resources and gatherings can offer support and companionship, even if all you talk about is the sale at Macy’s, contemplate the weather, or just rest and take in what’s happening around you. Volunteering your time to help others is a great way to change your focus as well as broaden your friendships. Practice community – by bringing your whole and sacred self into the presence of the Season.

3) Be realistic. The holidays don’t have to be perfect or just like years gone by. As families change and grow, traditions and rituals can change as well. Feeling nostalgic is natural, but we also follow a God who promises to renew all things. So, choose a few traditions to hold on to, but be open to creating new ones. For example, if your adult children can’t come to your house, find new ways to celebrate together, such as sharing pictures, emails, videos or Skype!

4) Set aside differences. (This is not asking the same as asking for reconciliation, which can be a life-long spiritual work). As a spiritual practice for the Season, try to accept family members and friends as they are, even if they don’t live up to all of your expectations. Set aside grievances until a more appropriate time for discussion. If you really cannot tolerate someone’s unhealthy behavior, limit your exposure to them through clear boundary setting of your time and participation – plan for a low-key, healthy exit strategy for the times when you may need one. You may even want to create a rescue code word or phrase (like “fruitcake!” or “the penguins must be hungry!”) in order to alert a close friend to quietly support you as you remove yourself from a given situation. However, be understanding if others get upset or distressed when something goes awry with planned events. Chances are good that they’re experiencing the effects of holiday stress and depression, too, but they haven’t identified those feelings.

5) Budget. Be a Good Steward of the resources God has provided to you, and stick to a budget you can afford. Before you go gift and food shopping, decide how much money you can afford to spend. Then, stick to your budget! Don’t try to buy happiness or gratitude with gifts – guilt is always bad credit. Instead, remember the Pearl of Great Price – the genuine article of Love that can only ever be truly given when it is given with no expectation of return. Try these alternatives: Donate to a charity in someone’s name, give homemade gifts, or write a handwritten letter – a personal letter is a precious and rare thing these days!

6) Plan ahead. Scripture consistently reminds us to be prepared – this spiritual practice applies to daily living as well as waiting for Christ (which very much characterizes Advent). Set aside specific days and times for preparations such as shopping, baking, visiting friends, Advent prayers/reading at home and other activities. If you’ve committed to assisting at church services, be sure to arrive a little early for personal prayer and centering – church isn’t just one more “task” to check off at this time of year. Rather, church services and service to others can help keep us grounded and fed by the Season instead of exhausted and depleted by it.

7) Learn to say a holy, healthy “no.” Saying yes when you should say no can leave you feeling resentful and overwhelmed later. Friends and colleagues will understand if you can’t participate in every project or activity. If it’s not possible to say no to something, try to remove something else from your agenda to make up for the given time – set your priorities and stay with them. The spiritual practice of a holy, healthy “no” helps preserve and sustain our best health during a time when God asks us for the gift of our attention – inviting us to be fully present to the in-breaking of the Divine on Earth and within our own hearts.

8) Don’t abandon healthy habits. Christmas is a time for celebration but not for reckless abandon – try not to let the Season become an excuse for losing your spiritual mindfulness. Overindulgence only adds to stress and guilt later. So, have a healthy snack before attending holiday parties so that you don’t go overboard on sweets, cheese or drinks. Use small plates for buffets and servings. Also, continue to get plenty of sleep and physical activity, offsetting any extra calories you may choose to take in.

9) Relax. Remember: the song is “God REST Ye, Merry Gentlemen!” Be intentional about scheduling some time for yourself. Spend at least 15 minutes alone every day of Advent as a Mini Sabbath – a sacred time without distractions or agenda; this can refresh you enough to handle what you need to accomplish. Take a walk at night and stargaze. Listen to soothing music. Find an image of the Sacred within your inward vision that reduces stress for you – then, clear your mind, slow your breathing, and restore your inner calm.

10) Don’t hesitate to seek professional help. Despite your best efforts and best spiritual practices, you may find yourself feeling persistently sad or anxious, plagued by physical discomfort, unable to sleep, feeling irritable or hopeless – the season may disjoint you completely, causing you to feel unable to face even routine chores. If these feelings last for a while, please talk to your doctor or a mental health professional. You may feel more comfortable initially speaking with a clergy person, such as [*gasp!*] your Pastor. If you would like to speak with me, please be assured that I will help find a referral resource for you for ongoing professional support while maintaining your confidentiality and respecting your privacy.

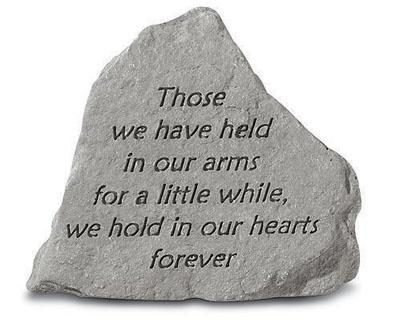

Ultimately, the most valuable gift we can bring to Christ at Christmastide is ourselves – complete and whole, just as we are – with all our feelings, all our messiness, all our hopes and fears, all our talents and insecurities. We are asked to leave it all at the Manger, in the sure and certain confidence that to God it is all priceless treasure. Even as much as Advent is a time of preparation, it is also a journey of remembrance – timelessly reminding us that we are unconditionally loved by the Christ who is Emanuel, “God with Us.” Now, always…and forever.

May you have a truly Blessed Advent and Merry Christmas,

Experiencing a truly sacred Season of the Spirit.